Masterclass 4: Lesson 1 of 7

1. Stories make events unforgettable

Quick, solve this equation:

1,200,000 x 0.3333333 / 4

Okay now pause.

Actually, try solving this instead: Jordan was quietly stealing Nikki’s events budget. Jordan had drained roughly one-third of the annual total of $1.2 million over four sneaky months. Roughly how much did Nikki lose per month?

If you’re like most, the word problem was actually easier than the math, even though both are the same equation. This is your first takeaway. Our brains are wired for story. We’ll participate longer when we get one. And if you want attention and retention, you should use one for your events.

In this lesson, we explore that idea, and how you can make use of it.

Brought to you by our team of experts

Want to get this course in your inbox?

Every event is secretly a story

So what constitutes a story? It’s a tale in three parts, beginning, middle, and end, which leaves the hero changed. The hero undergoing change is important because that’s what gets us sucked in and helps us relate. I bet you couldn’t care less what happened to those numbers. But aren’t you curious what happens when the boardroom doors fly open and Nikki confronts Jordan?

Every event is secretly a story—with a beginning, middle, and end. How does yours leave your attendees changed?

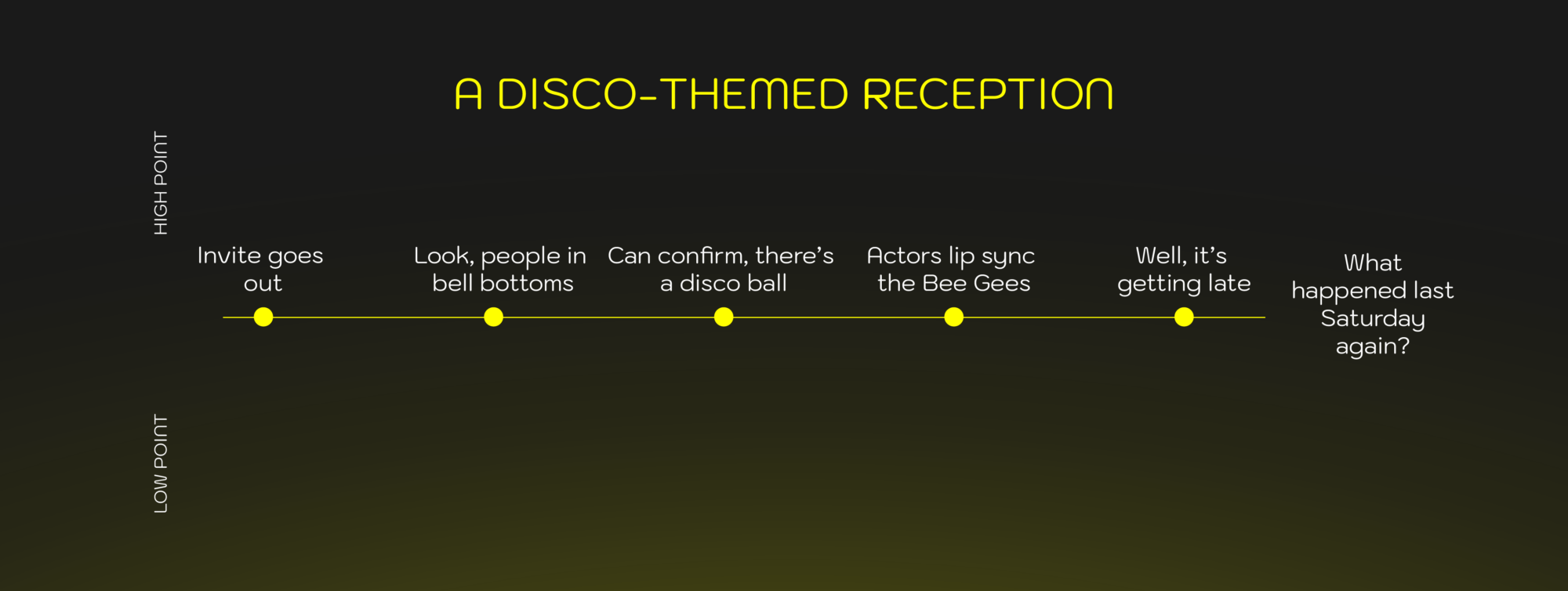

Most corporate events lack a story, so instead of rising and falling action that unfolds throughout an evening, the event trails and falls flat.You can plot stories like below to understand how much rising and falling action there is.

In the disco-themed corporate reception diagrammed, nothing unexpected happens. There are no moments of tension or discovery. No highs and no lows. No trials, triumphs, suspense, or momentum. People show up, mill about, down too many Piña Coladas, and leave. It fades from memory.

Just like, for example, whatever you ate for dinner two Thursdays ago. Can you recall?

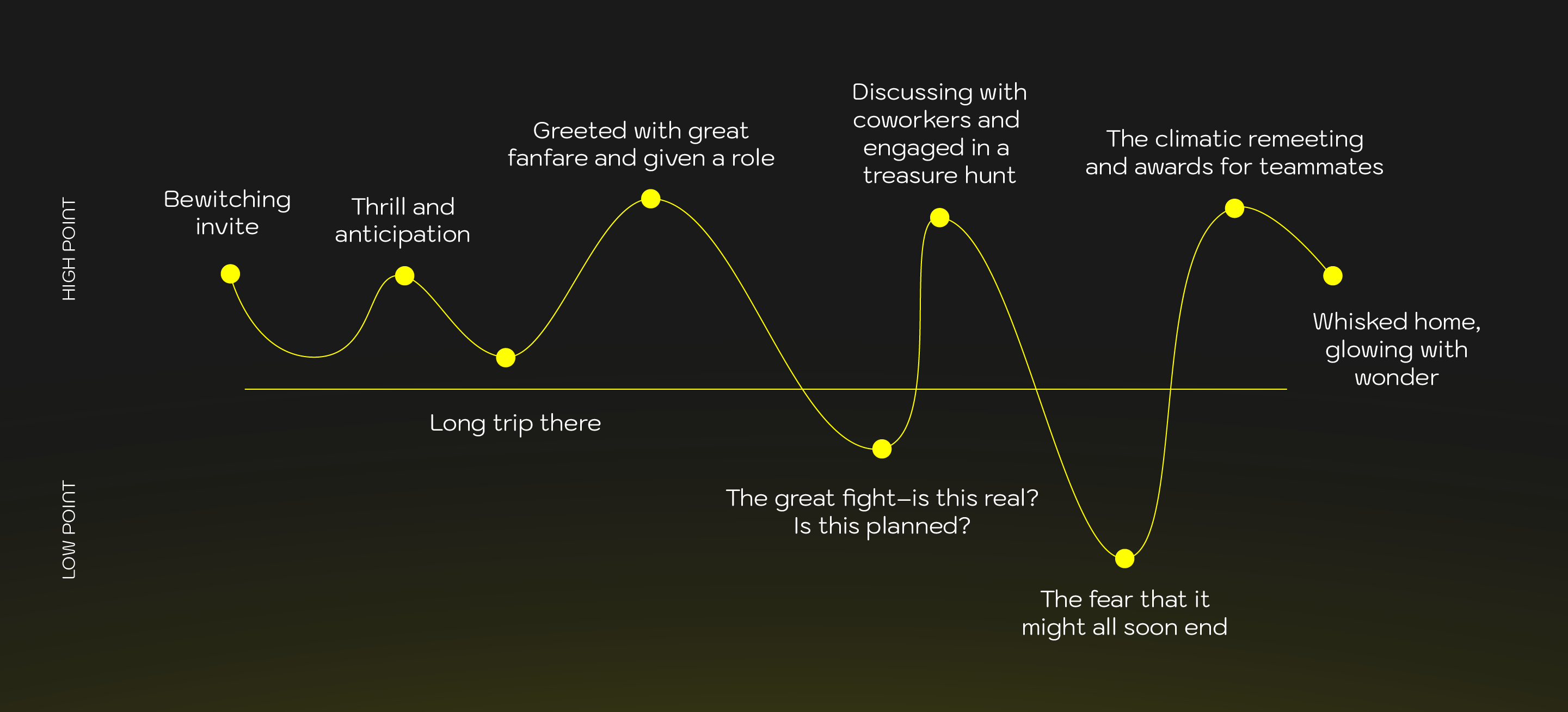

But imagine this instead. The team scraps the disco and instead, a parchment envelope sealed in wax shows up at each worker’s door. When opened, nuts and bolts pour out. Inside is an elaborately handwritten letter from a “long lost scientist acquaintance” inviting them to their English manor to view something his actor spouse has set up. It ends with the words, “PLEASE DON’T TELL.”

What on earth? Very different feeling. Same cost. But now, rich with intrigue and mystery.

By the time everyone arrives at that party, the scene is already set. Everyone’s been secretly telling coworkers and just based on the letter, everyone knows roughly how to dress, how to behave, and what they think they’re getting into.

And let’s say the actors running about the event have a literal fight with fireworks and at each phase of the night, everyone is studiously shepherded from room to room with exact guidance, from surprise to safety, surprise to safety. And at the end of the night, the scientist and the actress make up before yet more fireworks.

Here’s what that storyline looks like.

Listen. I could go on and on about what neuroscience tells us about how stories light up different regions of the brain. But I fear that 10 minutes later, you’d only have forgotten. Whereas if I told you the story about the scientist and actor, you’d remember. (But the neuroscience does support this—you have a 5% chance of remembering a statistic, but a 63% chance of remembering a story.)

And if I REALLY want you to remember a story, I’ll thread several together and end them right where I began—in the marketing department, as Nikki slams the board room doors wide and points a finger at Jordan and shouts, “YOU!”

And if I’m doubly devious, I won’t tell you how it ends.

This week, ask yourself:

Have you ever attended an event with a story? Where something went wrong and was resolved? With characters to root for?

For inspiration, have a peek at this scientist and actor couple’s event:

Next week: I’ll explain how to find your seed idea.