Masterclass 4: Lesson 3 of 7

3. You must deliver the unexpected

Something happened to movie trailers in the 1990s. Maybe you noticed it too: They started giving the whole movie away.

The trailer for the 1993 film Free Willy shows the whale going free. The trailer for 2000’s Castaway with Tom Hanks reveals his rescue. This trend has only accelerated and has caused a lot of grumbling among cinephiles.

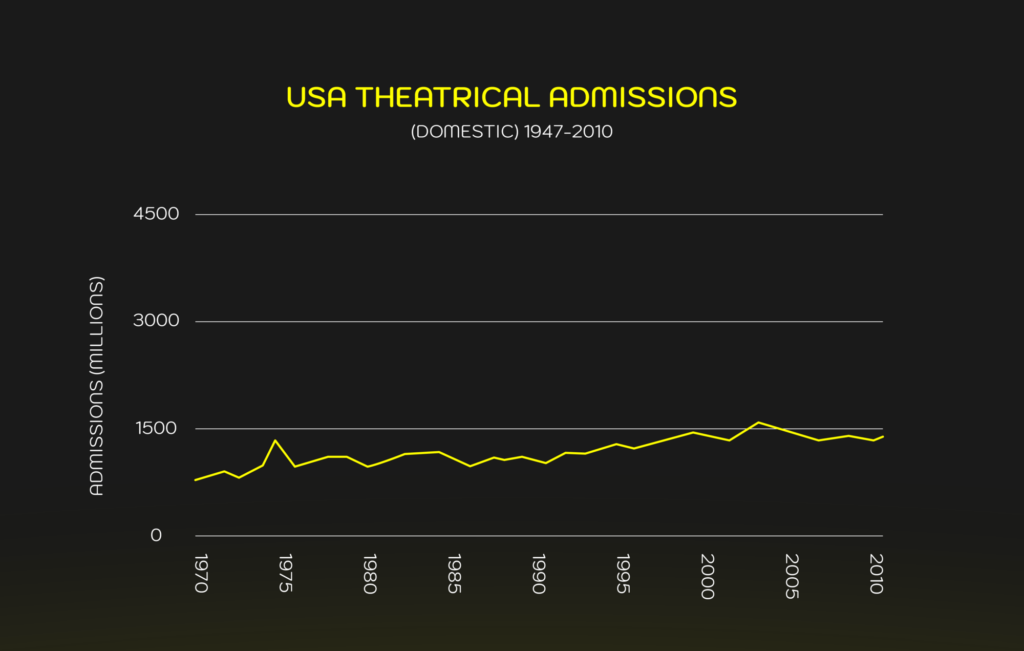

Yet historically speaking, this hasn’t really affected movie attendance rates all that much. (We’re leaving out the pandemic, which of course did.)

Why don’t spoilers dissuade more viewers? To answer that question, we’ll have to ask another question: Why do people like surprises?

Brought to you by our team of experts

Want to get this course in your inbox?

Most people are delighted to be wrong

Most of us are wandering through life and work reacting to the world, not as it is, but to our mental model of it. This requires a lot less thinking and is more efficient, like cruise control on a car. We hear what we expect to hear. We see what we expect to see. Because we aren’t really processing all the information—we’re guessing.

Surprises shatter these models.

“Being surprised actually causes humans to physically freeze for 1/25th of a second,” reports NPR. “After humans freeze, surprises usually trigger something that causes humans to generate extreme curiosity in an attempt to figure out what is happening during a surprise.”

In a psychology study, participants rated stories more highly if someone told them spoilers. How can you use that in your events strategy?

– Psychology Today

That extreme curiosity is a spurt of noradrenaline whipping through our brain. Your pulse quickens. You are alert to danger. Your brain suddenly starts perceiving everything in great detail because it’s trying to figure out what’s amiss. This effect is the greatest award an events team can receive—surprise brings people to extreme attention.

So why then do so many corporate events fall back on the same old run of show? The one that goes like this: Once everyone’s seated an executive or emcee walks out to tell a story. They say, “Welcome to so and so city.” They have a few canned rah rah moments, welcome someone else on, and before you know it, it’s time to go.

To sear that moment into people’s minds, you need to interrupt that pattern.

At a recent event, we tried this instead: We had a cold start where we planted the CEO as a member of the crowd. As a spotlight fell, they interviewed the person to their left, who hadn’t realized who they’d been chatting with. This conveyed a very unusual message and shattered the model. It said, “Wake up! You are part of the story.”

Or how about this: At dinner, we wrote new seating arrangements on a card under people’s plates, and after dessert, had them switch. It shook everything up; it created a mood of openness and anticipation. And it worked even better because everyone knew this was coming, which brings me back to the earlier point about movie trailers.

People still watch movies despite the spoilers because we are all wired to investigate surprises. How did the surprise go down? Did it end well? What were the implications? In Castaway, Tom Hanks’ character returns home and finds his wife has moved on. How does she react? We must know.

It’s up to you how much you give away, but knowing your CEO is placed somewhere in the audience can be just as compelling (though less of a shock). Shocked people want to investigate, and can enjoy the aftershocks again and again.

Your event surprise doesn’t have to be big either. It can be as simple as conversation cards with questions that forbid small talk and give deeper prompts—such as asking all the highest-powered people in the room to reflect on their first jobs, or asking any of the 36 questions that lead to love. (They’re actually all platonic.)

But perhaps you’re wondering whether it can really be this simple. If entertainers have known the power of surprise for millennia, why do corporate event planners fall back on the same forgettable run of show? I have theories. Many of them think surprises are too risky.

But I would argue the opposite. The greatest risk of all is doing what’s always been done and lulling your audience to sleep.

Surprise or no surprise, it costs the same. But if you have a shot at being that movie trailer that’s so vivid, everyone has to know more even if they know how it ends, why not take it?

This week, ask yourself:

What does your audience expect from your big recurring event? How might you subvert their expectations?

Next week: I’ll explain how you can harness the power of environment to do more of your work for you.